I recently had the pleasure of teaching a workshop on descriptive bibliography at the Signet Library, the second I’ve now given there for postgraduates keen to develop their book historical skills. Last year I had noticed a splendidly bound copy of Bishop John Leslie’s De origine moribus, et rebus gestis Scotorum (Rome, 1578) decorated with what looked to me like the arms of a continental prelate, but had been unable to satisfactorily identify the volume’s provenance. This year, I think I’ve cracked it.

The book itself, an important Catholic response to the Scottish Reformation by one of Mary, Queen of Scots’s staunchest supporters, looks something like this (after all, I had to set my students a good example of pagination, collation, etc.):

John Leslie, Bishop of Ross. De origine moribus, et rebus gestis Scotorum libri decem. Rome: In Aedibus populi Romani, 1578.

Separate title page following p. 280: John Leslie. De rebus gestis Scotorum posteriores libri tres. Rome: s.n., 1578.

4o. [40], 588, [32]pp.; a-e4A-R8S4T-Oo8Pp-Rr4Ss6; 10 copperplate engravings: (1) fold-out map ‘Scotiæ regni antiquissimi accurata descriptio’ following unpaginated preliminaries; (2) stemma I of the early Scottish kings facing p. 83; (3) ibid. II facing p. 113; (4) ibid. III facing p. 131; (5) ibid. IIII facing p. 173; (6) spectacular stemma of the Stewarts from Banquho facing p. 261; (7) royal arms printed above letterpress on verso of p. 282; (8) stemma of the family of Henry VII of England and Elizabeth his wife facing p. 341; (9) stemma of the family of James V facing p. 367; (10) stemma IX, the family of Queen Mary, facing p. 463.

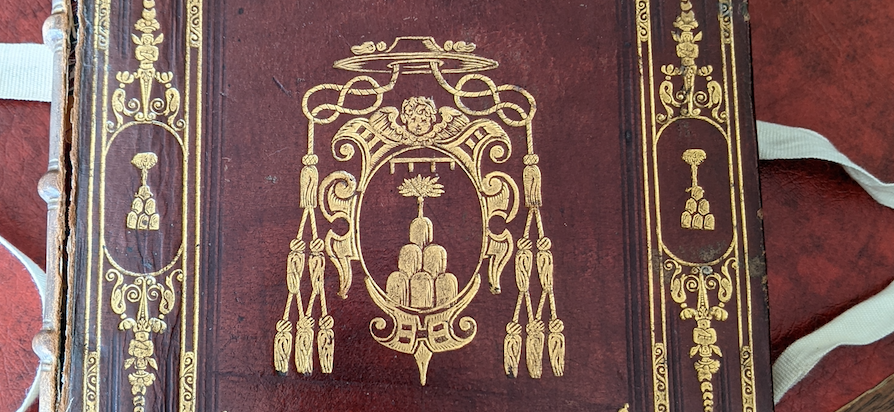

But what about this binding, a fine example of early modern red morocco? My strong instinct was that it was Italian, but I would be the first to confess that my knowledge of Italian bindings, especially Italian armorial bindings, is quite sparse.

My initial step was to parse the arms in the formulaic language of heraldry, something I knew how to do in English or French, but not in Italian. Various Google searches and dictionaries later and I was at the slightly more advanced starting point of being able to say that I was seeing an “albero su un monte di sei cime e accompagnato in capo da un lambello a quattro pendenti”, albeit with its colours still unknown.

Next, I considered the ecclesiastical hat – or galero – which is surmounted with six tassels (fiocchi). This almost always indicates a bishop or perhaps an abbot, certainly a senior ecclesiastic of some variety below the level of cardinal. Could I find such a man who bore these arms?

Initial, more or less uninformed, Google searches led me to the the Ceramelli Papiani collection in the Florentine Archivio di Stato which records arms like these for the otherwise rather obscure Paolini family. However, none of the family were bishops, abbots, etc., and the mountain with six tops is common enough in Italian heraldry that I was hesitant to leap to conclusions.

So I turned away from modern short cuts and began to work through the vast nineteenth-century heraldic dictionaries. Searching in Théodore de Renesse’s Dictionnaire des figures héraldiques, 7 vols. (Bruxelles, 1894-1903) under “monts sommés d’un meuble” (i.e., mountains topped with another figure, vi. 596-597) revealed nothing useful: crosses, eagles, and crowns but no trees. Giovanni Battista di Crollalanza’s Dizionario storico-blasonico delle famiglie nobili e notabili italiane estinte e fiorenti, 3 vols. (Paris, 1886-1890), however, eventually produced a more plausible option: the Cesi of Modena,

Although the label (lambello) was lacking, this was a family with the sort of profile that might have produced our mysterious book owner. Working through the various members of the family at https://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/ seemed to suggest that the Cesis’ high point was slightly earlier in the sixteenth century. Only two Cesi were bishops late enough to have owned Leslie’s 1578 publication: Angelo Cesi (1530-1606), Bishop of Todi from 1566, and his younger namesake (1592-1646), Bishop of Rimini from 1627.

To clinch the identification, the heraldic extravaganza that is the Palazzo dell’Archiginnasio in Bologna contains a mural which includes arms attributed to Cardinal Pier Donato Cesi but which must almost certainly belong instead to his brother, the elder Angelo:

(c) Biblioteca Communale dell’Archiginnasio

As you can see, there is a strange device in chief in these arms, something like a torse, which must, I think, relate to the label in the arms as depicted on the binding; identification with the Cesi seems more or less certain. Which Angelo is less clear, though the elder was an active patron of the arts, so perhaps the slightly more likely candidate.

After making this, I thought quite likely, identification, I wrote with my results to the Signet Library’s librarian, the wonderful James Hamilton, who replied with a counter-proposal that gave me pause. The Emory Digital Image Archive has a picture of arms very like these – though lacking the label/torse – attributed to Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti. Had I gone wrong? Was the owner someone completely different?

I was determined to find out, one way or another, so followed the citation in the Emory database to the Artis rhetoricae commentarius of Giovanni Luigi and Annibale Marescotti (Bologna: apud Ioannem Roßium, 1570). It appears there on the recto of the leaf before p. 1, but – behold! – in context it is clear these arms are not those of Cardinal Paleotti, but are prefixed to a hexastichon in praise of Cardinal Pier Donato Cesi, the elder Angelo’s brother! In other words, both James and I were right: these were definitely the same arms and they definitely belonged to the Cesi family.

So far the Cesi. But what of the volume’s subsequent history? On the verso of its flyleaf is a small stamp:

This is the mark of Henry Liddell, a former Bombay Civil Servant who retired in some splendour to Culross Abbey, collecting books and dying there in 1873. After Liddell’s sale in 1874, this volume presumably stayed in Scotland since it was subsequently donated to the Signet Library by Robert Carfrae Notman, WS (1899-1980), a sometime Fellow of the Scottish of Antiquaries of Scotland:

Sadly, as with so many books, we know nothing of this volume’s life between its ownership by Bishop Cesi in the seventeenth century and Liddell in the nineteenth, though we may yet hope that some notice of it can be discovered in earlier library or sale catalogues. For the moment, however, it remains one of the more spectacular bindings in the Signet Library’s collection and an intriguing witness to the continental reception of John Leslie’s Catholic version of Scottish history.

Text (c) 2023 Kelsey Jackson Williams

Images (c) 2023 Society of Writers to His Majesty’s Signet and Biblioteca Communale dell’Archiginnasio as indicated.

Leave a comment