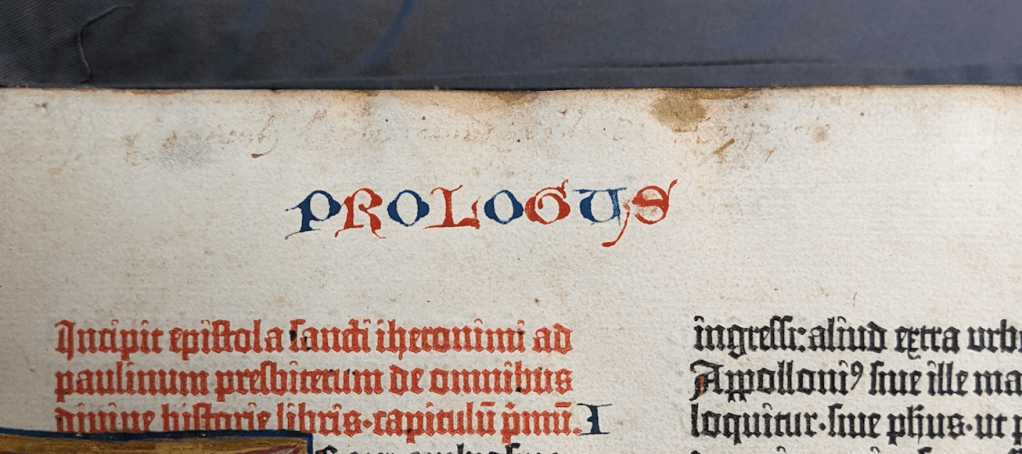

In 2013, the John Rylands Library in Manchester used multi-spectral imaging to recover an almost completely erased ownership inscription in volume I of their Gutenberg Bible (figure 1).[1]

The provenance of this Bible had been unknown prior to its nineteenth-century owner, George John, 2nd Earl Spencer (1758-1834), until the previous year when Eric Marshall White, Scheide Librarian at Princeton and the world’s leading authority on the Gutenberg Bible, had published a bookseller’s bill which he had found in the Althorp papers in the British Library and which showed Spencer purchasing his Gutenberg, together with a 1459 Psalter and an Eggestein German Bible, for the princely sum of £340 in October 1790.[2] But where had the bookseller – Thomas Payne – come across this treasure?

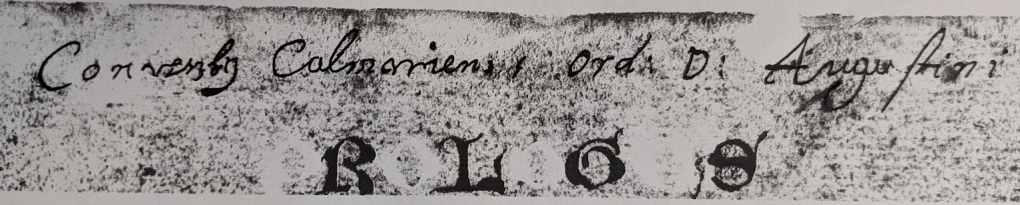

The 2013 MSI of the inscription at the top of the first printed leaf of volume I (figure 2) revealed a faint line of text in an eighteenth-century italic hand, tentatively read as “Conventus Colmariensis Ord: D: Augustini”, i.e., “The Colmar Convent of the Order of St. Augustine”.

Previous scholars had read this inscription as pertaining instead to the Cistercians of Eberbach im Rheingau and, while the Colmar reading found its way into the standard work on the subject, the matter of this Bible’s early provenance seems to have remained uncertain.[3]

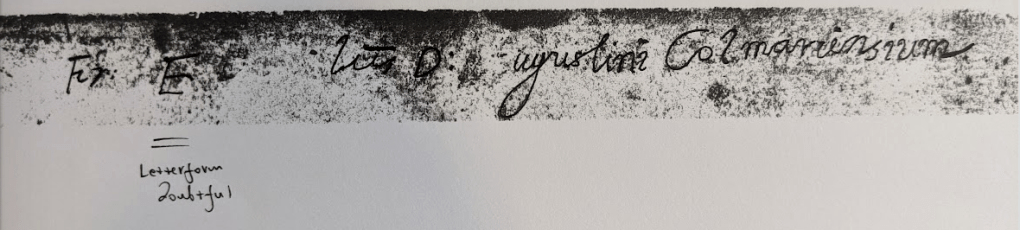

A few days ago I had the pleasure of working with the Rylands’ Gutenberg Bible on-site as well as studying the 2013 multi-spectral images. It became clear, first, that the Colmar reading was undoubtedly accurate (figure 3) and, second, that there was another, different inscription on the first printed leaf of volume II of the Bible (figure 4).

This was much more heavily erased, making identification of any characters with the naked eye an almost impossible task.

With the aid of further MSI images, however, together with digital manipulation, comparison with different forms of eighteenth-century italic, and pen trials with a similar pen to determine the plausibility or implausibility of certain reconstructed strokes, I was able to read the majority of this second, previously unnoticed inscription (figure 5), “Fr[atrum] Ere[mitarum] Con[ven]tus D[iui] Augustini Colmariensium”.

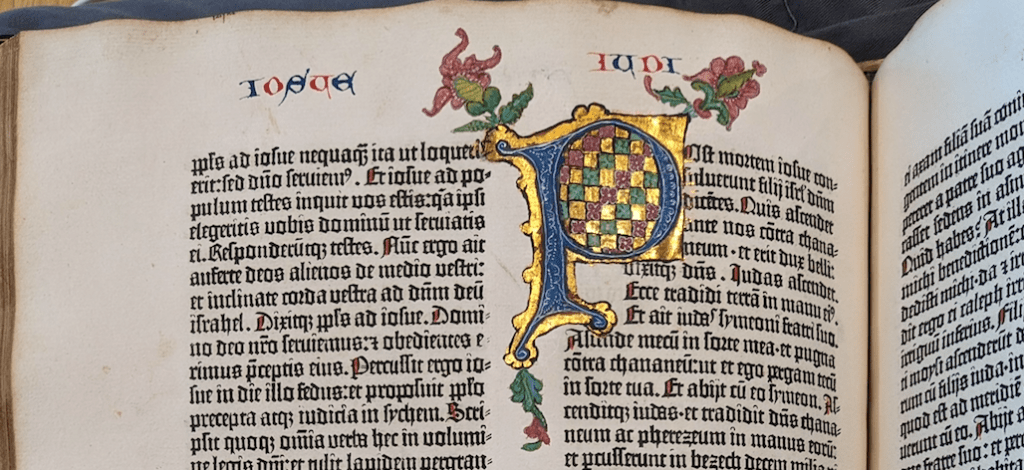

The final clue was provided by another book from the same convent library, now in the Bibliothèque Numérique de Lyon, which bore an almost identical – but unerased – inscription as volume II of the Gutenberg, “Fratrum Eremitarum Diui Augustini Colmariensium” (“The Eremite Brothers of St. Augustine of Colmar”; figure 6) thus confirming that both volumes had belonged in the eighteenth century, and perhaps much earlier, to the Couvent des Augustins in Colmar (a small city in historic Alsace-Lorraine).

This, in turns, helps us understand how Earl Spencer could have bought his Gutenberg in London from Thomas Payne in October 1790, but also raises new questions. The Augustinians in Colmar fared as poorly as most religious during the French Revolution, with their goods (including a library of 1,900 volumes) being inventoried – with an eye to state-sponsored depredation – on 11 May 1790 and the convent being marked for closure on 3 May 1791. The people of Colmar, however, were upset with the closure of the convent church and on 22 May 1791 a “mob forced the gates of the church”, which was re-opened for worship two days later. [4] The convent was finally closed and the remaining religious ejected between 10 and 16 June.[5] But this was some months after the convent’s most precious book had been purchased in London. What had happened?

That remains to be seen and solving this puzzle is part of the ongoing research for my new book, Bibliomania: Portrait of an Obsession, which recovers the tangled web of Earl Spencer’s collecting of Europe’s rarest books (many, like this one, taken in dubious circumstances from monastic libraries). For the moment, though, I’m delighted to be able to add this additional fragment of information to what we know of the Gutenberg Bible and its passage down the centuries. Provenance research is a vital part of a book historian’s work and it’s immensely satisfying to be able to resolve long-standing questions like this one.

Huge thanks to John Gandy and Tony Richards at the John Rylands for their help with this project. Expect where specified otherwise, all images are (c) John Rylands Libary, Manchester.

Footnotes

[1] Eric Marshall White, Editio Princeps: A History of the Gutenberg Bible (London: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2017),141.

[2] Eric Marshall White, “Gutenberg Bibles on the Move in England, 1789-1834”, Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society 15 (2012): 79-100 at 84.

[3] For the Eberbach reading see White, Editio Princeps, 141.

[4] Claude Muller, “La suppression des couvents des Dominicains et des Augustins de Colmar (1790-1791)”, Annuaire de la Societe d’histoire et d’archeologie de Colmar 36 (1988): 39-48 at 44-45; Réimpression de l’ancien moniteur (Paris: au bureau central, 1841), viii. 568.

[5] Muller, “La suppression des couvents”, 46-47; Assemblee Nationale, Corps Administratifs et nouvelle politiques et littéraires de l’Europe no. 666 (June 1791): 3.

(c) 2024 Kelsey Jackson Williams

EDIT: This post was updated on 16 July to incorporate material from Muller’s article (cited in fns. 4 and 5).

Leave a comment